We hear much of the chivalry of men towards women; but let me tell you, gentle reader, it vanishes like dew before the summer sun when one of us comes into competition with the manly sex.

Marth J. Coston, 1886

Marth Jane Coston jousted with men her whole life, men who fancied themselves filled with chivalry. Instead, these “gentlemen” tried to block her, ignore her, demean her, and, on occasion, deceive her as she developed her inventions.

Yet, she was forced to rely on men who had knowledge she lacked. She knew little of chemistry, scientific method, or business.

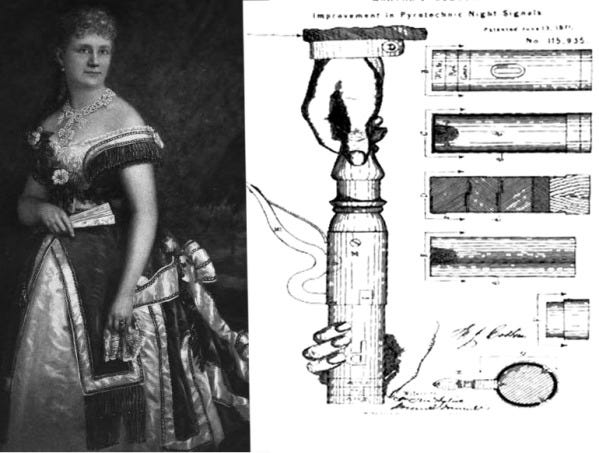

Martha Coston perfected the Coston Signals, 3-color, handheld flares used to communicate between ships at night. The signal flares could be seen up to twenty miles away. She then moved from the laboratory into the intrigue and gamesmanship of politics, first in the United States and then in the royal courts of Europe.

Martha Coston was 14-years old, living in Philadelphia with her widowed mother and older sisters, when an older man began to call on the family. Benjamin Franklin Coston was a 21-year-old pyrotechnic and naval engineer. He fell in love with Martha and she in turn adored him.

They eloped when she was 16 in 1844. As she wrote in her autobiography:

We proceeded at once to the house of a minister, unworthy of the gospel he preached, and willing for the sake of an extra fee to ask no embarrassing questions and agree to make no revelations… and in a few moments it was over, and I, a sixteen-year-old girl, a wife.

Benjamin Coston transferred to the Naval Yard in Washington D.C. where he adapted Hale’s Rocket for shipboard and invented a percussion primer enabling cannons to fire in any weather. The Secretary of the Navy named him Master in the Naval Service and placed him in charge of the Naval Laboratory.

Four years and four children later, Martha Coston was widowed. Her young husband died of exposure to the gas he worked with in the lab. Martha was devastated—21-years old with no means of support. Within two years, her mother and two of her young children also died.

One day she remembered a box of papers her husband had suggested might have value. She wrote:

It was on a dreary November afternoon, the rain was falling on the window-panes heavily, … even the canaries in their cages were so depressed by the pervading gloom that they refused to sing…

In the box she found Benjamin Coston’s rough notes for signal flares. Thus, she began ten years of self-education and experimentation to flesh out and perfect her husband’s unfinished ideas. One of her challenges was to add a third color to the signal. She wanted to use blue to complement red and white. Using a man’s name instead of her own, she wrote to pyrotechnists seeking advice. They had a faded blue. It was not bright enough, she said. So, she accepted green.

Sometime in 1858, using all of her social and Naval connections, she approached the Secretary of the Navy asking for a test of the Coston Signals. Commodore Hiram Paulding conducted the tests and informed Martha by letter that “the signals proved utterly good for nothing.” But the Commodore did not want to be known as the officer “who put her lights out.”

Six months later Martha returned with redesigned signal flares for another trial. The three Naval officers who conducted the new trials reported:

1. That the Coston Signals are better than any others known to them.

2. That the board strongly recommend them for use in the navy.

They offer precision, fulness, and plainness, at a less cost for fireworks, … [and are] absolutely necessary to the efficient conduct of a fleet.

She patented her pyrotechnic night signal and the code system she designed on April 5, 1859 in the name of her deceased husband. Her subsequent patents were in her own name.

Coston Signals created a distinct military advantage throughout the Civil War on both the Mississippi River and the Atlantic coast. Confederate blockade runners were chased down night and day by Union boats communicating with the signals. The land and sea attack on Fort Fisher was coordinated by Coston Signals capturing the fort and eliminating a major Confederate supply line.

Martha tried to sell her patent to the United States which required congressional approval. Without buying the patent, though, the Navy ordered thousands of night signals. Her New York factory delivered the signals, but she had to knock on many doors just to get paid.

The Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance refused to pay her bill so she went in person for an explanation. Captain Wise tried to brush her off. He paced the room growing redder in the face. Finally, he burst out:

Mrs. Coston, you are making altogether too much money on those signals. I have nothing but my pay, and my wife is obliged to make her own dresses and bonnets.

Martha was momentarily speechless. But she replied:

I can hardly see the connection between the Coston Signals and Mrs. Wise’s millinery; but if you wish to discuss the matter on so personal a basis, I am aware that as Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance you receive at least four thousand dollars per annum, … were I in your place, I should consider myself rich, — rich enough at least to insist upon my wife having her bonnets and dresses made for her.

Captain Wise refused to pay. Martha worked her way up the chain of command finally to the Secretary of the Navy.

She traveled to Europe to sell her signals. Whenever the Coston Signals were tested, they were quickly recognized as the best. Yet, the governments of Europe stalled.

In Italy, on her second visit, she was told that the minister of the marine was out. She replied that the minister had made an appointment with a lady and he would surely return soon. Her intuition told her that the minister was hiding in the inner office hoping she would go away. She did not.

After waiting for half an hour, she was escorted in:

I met the gentleman with a coldness and hauteur that outrivaled his own, and as briefly as possible told him that I had made a second journey to Italy at the request of his government, and on his own representations; that I had waited the entire winter and spring for the negotiations to be closed, in vain; and that I would spare him any expression of my own disappointment at the dilatoriness of the government…

She then told the minister that she had only come to take her formal leave since she was leaving the country as soon as possible and that she would no longer consider selling to the Italians since

the Italian government had been so lacking in courtesy in its treatment of a foreigner;

As she prepared to depart, the minister suddenly changed his tune. He would personally present the proposal to the full cabinet at its next meeting.

She continued her tour of European royalty and ministers. She met the King and Queen of Sweden, attended royal banquets in England and France. She was most impressed by the Empress of France whose radiant blends of silk, sash, and jewelry commanded her admiration. However, at the English banquet, she spotted a woman who:

was very short, both in stature and of breath; her face was red and cross, and her toilet consisted of a large, gayly-plaided poplin, so short in the skirt as to expose the tops of a pair of heavy walking-shoes. … but the finishing blemish was a huge muff of royal ermine suspended round the lady's fat neck by a cord, and which … wobbled helplessly back and forth over her well-rounded body.

Martha asked her escort, a British officer, ''Who is that funny, fussy woman?”

He lowered his voice and replied

Good heavens, madame, that is our Gracious Sovereign!

Martha returned to the United States upon the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. However, she had registered patents in England, France, Italy, Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands.

She established her manufacturing company in 1859 which survived until at least 1985. Coston Signal Flare and code system was purchased by the militaries of the United States, England, France, Holland, Italy, Austria, Denmark, and Brazil. The U.S. Life Saving Service, forerunner to the U.S. Coast Guard, along with yachting clubs, merchant vessels, and the U.S. Weather Service all adapted the Coston Signals.

Coston Signals were even carried to the North Pole where an expedition inserted the signals into the exterior walls of their ice huts to scare away wolves. Martha congratulated the expedition leader:

I am happy to say to you that in the Arctic regions you carried out my original idea when you used the signals to drive away the wolves from your igloos; for my principal object in perfecting the invention was to keep the wolf from my own door.

Martha Coston developed inventive skills even though she had no training. She believed that she had no other options. Throughout her long career, she demonstrated the empathy to understand other people and to engage them to achieve her goals. Empathy requires perception, prediction, and imagination—all skills necessary for creativity.

******

I invite you to read Death in the Digital Age, my latest column in Arrowsmith Journal

https://www.arrowsmithpress.com/journal/grief-tech

Dan Hunter’s book, Learning and Teaching Creativity, is available from

https://itascabooks.com/products/learning-and-teaching-creativity-you-can-only-imagine

Teachers receive a 20% discount.

Audiobook is available at,

https://www.audible.com/pd/Learning-and-Teaching-Creativity-Audiobook/B0CK4BQDJP

Thanks, Pete

Dan

Persistence, passion, patience and perspicacity appears to be a successful formula for success in any situation or endeavor. Thanks for sharing this highly informative and fascinating article. If there’s never been a documentary or film about this truly remarkable woman and her story, then you should find someone who can, or do it yourself. Certainly, it merits the effort.