In fourth grade, 1962, my friends and I were playing in their backyard on River Oaks Drive in Des Moines. There was a ravine behind their house directing storm runoff from one concrete culvert to another about 300 yards away.

To our nine-year-old view, the ravine was steep, overrun with weeds. Standing on the precipice where the grass was closely mowed, we got the idea that we could conquer the ravine if we only had the right tools.

A more strategic mind might have chosen a weed-chopping machete.

We decided to build a telephone.

We secured two empty soup cans from the trash, a bulky ball of string, a hammer and a nail. We punched a hole at the end of each can with the nail, threaded the string through the hole, and tied a knot to secure the string in the can.

One of us had to carry a can and string across the ravine while the others maintained our lookout position. During rainstorms, the ravine swelled from a trickle to a creek rising above our Keds high-tops. It was dry that day, but we took the risk.

I don’t remember who crossed the ravine first. But he backed up as far as he could, while the two on the other side did the same. We had considered establishing a secret code, but we forgot that. This was our invention. Naturally the first thing one of us said into his tin-can was, “Can you hear me?”

Our string telephone would have been the impetus to the invention of the telephone, if only we lived in the 1870s.

*****

In late January or early February 1874, Elisha Gray, superintendent of research for the Western Union Telegraph Company, made an accidental discovery. His young nephew was fiddling with Gray’s electrical equipment: batteries and an induction coil in the bathroom of his house. The nephew held one wire and slid the other hand along the cast-iron bathtub, “taking shocks.” Gray tried it. He noticed that the pitch made by his moving hand was the same as the pitch generated by the vibrating induction coil. Changes in the coil changed the bathtub pitch. He was conveying pitch through electricity.

In the spring of 1874, Gray resigned from Western Union to become a professional inventor.

He had over the years occasionally puzzled over the problem of electrical speech transmission. Then, sometime in the summer of 1875, he spotted something intriguing while walking on the streets of Milwaukee:

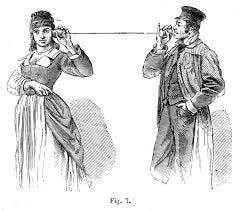

... I noticed two boys with fruit-cans in their hands having a thread attached to the center of the bottom of each can and stretched across the street. ... The two boys seemed to be conversing in a low tone with each other and my interest was immediately aroused. I took the can out of one of the boy's hands ... putting my ear to the mouth of it I could hear the voice of the boy across the street, I conversed with him a moment, then noticed how the cord was connected at the bottom of the two fruit cans, when, suddenly, the problem of electrical speech transmission was solved in my mind.

Gray realized this toy, sometimes called the Lover’s Telegraph or String Telephone, held great possibility. The walls of the can formed a voice chamber. The bottom of the can acted like a vibrating diaphragm. And the string connected the vibrations of one can bottom to the other.

However, Gray parked his telephone ideas on the shelf because the demand for telegraph service was increasing. More service required more wires because each wire carried only one message at a time. Consequently, telegraphic wires were choking the city streets, like spider webs multiplying out of control. Western Union offered a $1 million prize to anyone who could devise a method for the wires to carry multiple messages at the same time.

With $1 million in the offing, Gray devoted himself to perfecting a harmonic multiple telegraph system, a system where multiple messages could travel the same wire. In 1875, Gray invented receivers that could unscramble the multiple messages earning several patents. But he was also confronted by patent interference charges from an amateur inventor—Alexander Graham Bell. (Patent interference cases, common in the 19th century, occurred when two inventions appeared to be identical.)

At this time, Alexander Graham Bell, an elocutionist by training, was in Boston trying to teach deaf children to speak. He was also attempting to design a harmonic multiple telegraph as his two financial backers demanded. The backers were also fathers of two of his deaf students. His mother in Scotland and his new fiancé—Mabel Hubbard— were both deaf. Bell believed that combining sight, the Visible Speech system his father invented, with sound through a telephone would facilitate teaching the deaf to talk.

On the advice of his patent attorneys, Bell signed his diagram of the telephone in front of a notary on January 20, 1876. He forwarded the papers to Washington DC to be filed for a patent.

Meanwhile, Gray secretly returned to his work on transmitting voice sounds. He broke his silence on Friday, February 11, 1876 when he asked his Washington lawyers to prepare a caveat to file as soon as possible. (A caveat is a placeholder for an invention being developed for patent.)

Somehow between Friday afternoon and Monday morning, someone tipped off Bell’s lawyers about Gray’s planned caveat. Monday, February 14 was Valentine’s Day. Bell’s team arrived at the Patent Office just before noon with the patent application and the $25 registration fee. Bell’s lawyer stood by until he was sure that the time and paid fee were officially recorded.

Gray’s lawyers arrived later that afternoon paying the caveat fee of $10. There are stories that claim that Gray’s attorneys arrived before the US Patent Office opened. That, they were the first in. The caveat was placed in the in-basket which gradually filled. So, the caveat wasn’t recorded until the end of the day. This intriguing horse race was moot. Today patents are issued to the first to file the patent. In the 1870s the patent was issued to the first to invent. The time and date of filing was irrelevant.

Five days later on February 19, the Patent Office suspended Bell’s application to give Gray three months to complete his patent application. Both Bell and Gray needed to create electrical “undulations” through variable resistance, which they both achieved by the “amplification of acoustic energy by the liquid transmitter.” But Bell added an additional claim:

by causing electrical undulations, similar in form to the vibrations of the air accompanying the said vocal or other sounds, substantially as set forth.

Bell was granted a patent on March 7. On March 10 on Exeter Place in Boston, Bell tested the first successful telephone prototype. After so many failures, Thomas Watson heard Bell succinctly when he said,

Mr. Watson—Come here—I want to see you.

Oddly, Bell secured the patent without submitting a prototype as normally required.

Bell introduced his telephone to the world two months later at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, May 10, 1876. Bell and his telephone were shunted aside to a card table tucked away in a corridor behind a wall.

The consensus among the judges, Western Union Telegraph Company, and the world of science was that the telephone was merely an ingenious scientific toy. Reviewing the telephone for the Centennial, the New York Tribune sounded like a parent chiding a child:

Of what use is such an invention? Well, there may be occasions of state when it is necessary for officials who are far apart to talk with each other without the interference of an operator. Or some lover may wish to pop the question directly into the ear of a lady and hear for himself her reply, though miles away; it is not for us to guess how courtships will be carried on in the twentieth century.

However, one of the Centennial judges, the Emperor of Brazil, Dom Pedro de Alcantara, recognized Bell standing in the crowd. Moments later, the Emperor picked up Bell’s telephone and announced to the crowd “My God! It talks.” Suddenly everyone wanted to try it. Gray told the exposition judges that Bell’s invention was “nothing more than the old lover’s telegraph,” that is: two tin cans and a string.

Nonetheless, Bell was awarded the Centennial medal for the best invention of the exposition.

Even with the medal, few recognized the economic value. In 1877, Bell offered to sell his patents to the powerful Western Union Telegraph Company for $100,000. Company president William Orton personally rejected the offer saying:

What use could this company make of an electrical toy?

Orton and many others assumed that the telephone would replace the telegraph’s dots and dashes with spoken messages. Operators would write down the words spoken over the phone and then create a message for delivery. They could not envision the massive market for people bypassing Western Union to talk to each other directly.

By the end of 1877, the telephone was becoming a commercial success. Bell formed the Bell Telephone Company and filed 600 patent infringement cases through 1893 when the patent expired.

Once its profitability was established, competitors and self-styled inventors came out of the woodwork to challenge Bell’s patent in court. Bell and his telephone company were in court from 1878 to 1888, when finally, the Supreme Court ruled in Bell’s favor. The five “Telephone Appeals” cases amounted 15,000 pages of evidence in 15 volumes. The transcript and decision ran to 149 volumes.

The Bell and Gray telephones demonstrated parallel inventions—two separate paths to the same goal. Their patent drawings submitted in 1876 are virtually the same. They both hit upon a liquid transmitter for variable resistance.

We want to credit the great individual inventor. But inventions often emerge simultaneously because the knowledge of the field has crossed a threshold opening multiple doors to new ideas.

Elisha Gray was the professional inventor with years of telegraph experience, first with Western Union and then on his own.

Bell was an amateur with inadequate knowledge.

Joseph Henry, physicist and first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, told Bell:

You are in possession of the germ of a great invention and I would advise you to work at it until you have made it complete.

Bell confessed

But I have not got the electrical knowledge that is necessary.

Henry told him "Get it.”

Bell won the legal battles. But he was not the sole inventor of the telephone. The line of ideas, attempts, and small successes extends to many people, in many directions and even far back in history. You can see the history of the phone by a ravine in Iowa in 1962, on a street corner in Milwaukee in 1875, and 350 years ago in 1667 when polymath Robert Hooke built a string telephone for his experiments with sound.

******

I invite you to read Death in the Digital Age, my latest column in Arrowsmith Journalhttps://www.arrowsmithpress.com/journal/grief-tech

Dan Hunter’s book, Learning and Teaching Creativity, is available from

https://itascabooks.com/products/learning-and-teaching-creativity-you-can-only-imagine

Teachers receive a 20% discount.

Audiobook is available at,

https://www.audible.com/pd/Learning-and-Teaching-Creativity-Audiobook/B0CK4BQDJP